Great news! Last week Jordan booked a guest role on the Australian television soap Neighbours. Filming will begin during the first week of March and is due to air May 30th on Channel 11 in Australia and early June, Channel 5 in England. Stay tuned for more info.

The Hair Salon indiegogo crowd funding campaign recently completed a very successful two month run and with the help of our extremely generous supporters we were able to a raise a staggering $10,001! From myself and the team we’d like to thank all that partook in the campaign and all those that helped raise awareness – You are all amazing.

We will be posting “thank you” videos to all our funders on the Facebook page as we record them over the coming weeks – With over a 150 funders you’ll be getting a lot more laughs!

Since the closing of the campaign we have had people ask whether they can still contribute and invest and if you’re one of these people the answer is YES! You can do so on the website www.thehairsalon.tv

Subscribe to the The Hair Salon YouTube channel and be the first to receive links to all new material and episodes.

Thank-you!

After months and months of character work and exploration The Hair Salon has finally landed!

“The Hair Salon is an improvisational mockumentary webseries tangling in the lives of seven over-the-top salonistas who work in a ‘cutting edge’ hair salon (in a suburban shopping mall). Break-ups and make-ups, fringes and minges, blow waves and blow j#bs – this is comedy nouveau with a style of its own.”

I play the character Norbert, a French Mauritian hair stylist. Check out the character introduction episode below.

Visit www.thehairsalon.tv for more information.

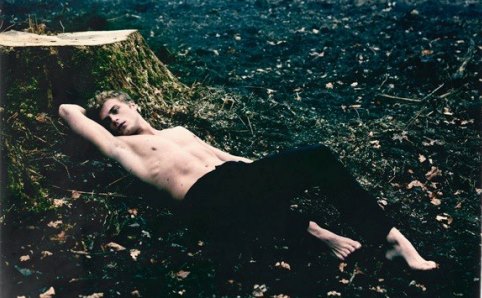

In March Jordan shot the following TV commercial for clothing company Spurling with production company Burning House.

Directed by Brett D’Souza, starring acting friends Eliza D’Souza and Lara Deam.

by Astrid Lawton

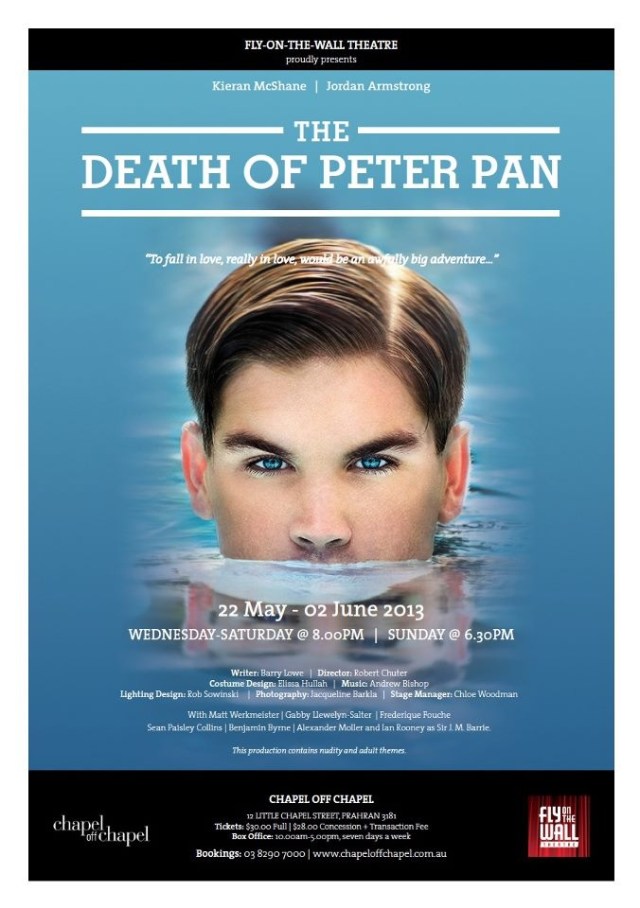

Set amongst the British upper crust in 1920s Eton and Oxford, this Fly-On-The-Wall Theatre production explores the devastating consequences of ‘the love that dare not speak its name’

Barry Lowe’s 1988 script tells the coming-of-age story of Michael Davies (Kieran McShane), adopted son of Peter Pan author James Barrie (‘Uncle Jim’, played commandingly by Ian Rooney), and inspiration for the author’s stellar work.

Whilst studying at Eton, Michael encounters the rakish Rupert Buxton (Jordan Armstrong), he of the foppish fringe and devil-may-care bonhomie, who challenges Michael emotionally and physically in a manner quite apart from his Eton chums (Matthew Werkmeister and Sean Paisley Collins).

The story moves from Eton to Paris after matriculation, where Michael reconnects with Rupert on a memorable night in a French brothel, to university at Oxford, to Uncle Jim’s house off the coast of Scotland, and back to Oxford. Each location serves to heighten the tension in the burgeoning relationship between the protagonists, in a breathless will they/won’t they manner, which finally culminates by the loch on Uncle Jim’s property.

The casting is good but with some inconsistency in strength. Armstrong’s Rupert very effectively and commendably straddles cocky assuredness and insecurity, juggling calculatedness and tenderness, and allowing fleeting glimpses of J.M. Barrie’s proverbial Lost Boy to sneak through in his portrayal. Paisley Collins as Roger Senhouse is very impressive as the flamboyant public school boy blurting out Wilde-esque witticisms which are later revealed to mask a much deeper introspection. McShane has notable moments (usually in conversation with Uncle Jim) but his depiction of Michael’s sensitivity and innocence sometimes comes across as slight sulkiness, and on occasion he struggles to maintain the character’s accent.

The set and lighting are respectively evocative and atmospheric – non-intrusive but still definite features of the production. The costumes are perfect, and the beautiful score (by Andrew Bishop) is almost a character in itself, so prevalent and memorable is its haunting presence. Director Robert Chuter debuted the production in 1989 with the same theatre company, and this restaging is a fine renaissance for a new generation.

Review by Alex Paige

Being unfamiliar with this play, I was a little perturbed by its title. To my great relief, The Death of Peter Pan turned out not to be an attempt to skewer one of my cherished childhood heroes. Instead, this multilayered, elegantly written and often challenging play tells the sad true story of 1920s Oxford University student Michael Llewelyn Davies – one of the adoptive sons of Peter Pan author JM Barrie – and his tragic love affair with attractively brash and outspoken Rupert Buxton.

Presented as a reminiscence of Barrie’s, who introduces the story and characters, Death of Peter Pan takes us back to Edwardian times and the friendship between Eton schoolmates Michael, Roger Senhouse and Robert Boothby. Though none are ignorant of the existence of ‘the love that dare not speak its name’, they’re also well aware that there is no chance for two men to build a life together, at least not in England. This only becomes an issue for Michael when he finds himself falling head over heels for Buxton – and in true starcrossed fashion, it’s the very depth of their feelings for each other that seals their fate.

Some of the best scenes were those that explored the burgeoning feelings between Michael and Rupert – delicately played by the appealing Kieran McShane and Jordan Armstrong. Playwright Barry Lowe has expertly encapsulated how it feels for an adolescent male to fall deeply in love with another, only to realise with a devastating mixture of bewilderment and anger that society will never permit the expression of one’s feelings. Despite our distance in time from the play’s setting, these psychological states still play out today for many young men so their representation on stage remains as relevant as ever.

McShane and Armstrong were complemented by a strong supporting cast – particularly notable was the wickedly arch but subtextually sympathetic public school figure of Senhouse as played by Sean Paisley Collins. A special mention must also go to Ian Rooney, whose memorable characterisation of JM Barrie was richly nuanced. Director Robert Chuter did a great job ably backed up by expert costume and set design, while Andrew Bishop’s music was ethereally evocative. Death of Peter Pan is a moving and thought-provoking piece of theatre and this production is thoroughly recommended.

Boyish bildungsroman and lingering love story

By Myron My

Barry Lowe’s The Death of Peter Pan is a tragic and beautiful story of growing up and becoming a man. Set during the 1920′s, it follows the life of Michael Llewelyn-Davies – the adopted (and favourite) son of Peter Pan author, James Barrie – and his chance encounter with fellow student Rupert Buxton.

Kieran McShane and Jordan Armstrong do a flawless job as the two protagonists, Michael and Rupert respectively. Rupert’s arrogance and brashness is a perfect contrast to Michael’s ambivalence and fear of what is happening, and this dynamic ultimately leads to a first kiss, first love and first heartbreak for Michael. There are some strong relationship-defining moments on stage, including the scene at the Parisian whorehouse and Michael’s swimming lesson. The affection and tenderness between the characters has a heartfelt authenticity, and this is mainly due to the talents of these two performers.

The two are supported by a more-than-capable ensemble cast including Sean Paisley Collins as Roger Senhouse, Michael’s flirtatious college friend. Collins is superb in his role: not overdone and revealing a serious and sensitive side that (when it does come to the surface) leaves quite an impact. Similarly, Ian Rooney’s J.M. Barrie is impressive as he plays out the nuances of a man still trying to live in his own Peter Pan moment.

Robert Chuter returns to the Chapel to direct The Death of Peter Pan and his focus on and image of this production is breathtaking. He has put together a very fine cast and crew, including costume designer Elissa Hullah and hair and make-up artists Olivia Wichtowski & Kane Bonato whose efforts warrant particular mention. The show does use blackouts between scenes and although I am not generally a fan of these visual interruptions, the haunting musical score by Andrew Bishop was able to keep us utterly absorbed in the moment.

The Death of Peter Pan is Australian theatre at its unrivaled best. It’s always a joy to be enveloped by a production that has brought everything so seamlessly together and its effects will still be felt long after having seen it.

Media posters are in and being distributed around Melbourne for the up coming season of The Death of Peter Pan. Bookings are now open at Chapel Off Chapel.

Jordan Armstrong | Actor

Jordan Armstrong | Actor